‘Errors of Scale’: The Story of Tehran’s Abbasabad Lands

- Issue: SCALE

- Mar 11, 2020

- 12 min read

Ahmadreza Hakiminejad

From cosmos to atom, what is going to be the reference for scaling cities? This is in fact a very old query. Aristotle in his Politics, argues that many people think that a city “in order to be happy ought to be large; but even if they are right, they have no idea what is a large and what a small” city[1]. Referring to the city’s size of population in ancient Greece, the philosopher was not so fond of a city made up of what he called “too few persons”. For him, creating a “too populous” one did not seem to be a good idea either: “it is difficult – perhaps impossible – for a city that is too populous to be well managed”[1]. The fact is that the word 'scale' is obscure. The linguistic meaning of the word is arbitrary. “It is simultaneously finite and infinite”[2]. It is not always about the size of things. It is far too abstract. It needs to be defined and tamed. In fact, the misjudgement of scale is a commonplace practice when it comes to city design. In his book Touching the City: Thoughts on Urban Scale (2014) Makower uses the phrase ‘errors of scale’ when he writes about Le Corbusier’s Plan Voisin of 1925; a ‘demented’ plan – as Alain de Botton puts it – which aimed to plough through one of the most important historic fabrics of Paris, Le Marais, and replace it with, what the architect himself called a “huge” cruciform “blocks of offices” served with vast thoroughfares – mainly a 120 metre-wide central highway, gigantic parks and low-rise apartment blocks.[3] In the following lines, I would argue that this wisely-put phrase of Makower - ‘errors of scale’ - fits well with the ongoing colossal urban planning project that has been shaping some 600 hectares of piece of land lying on the deep valleys and steep ridges of hills of Abbasabad in northern Tehran; Iran’s capital city.

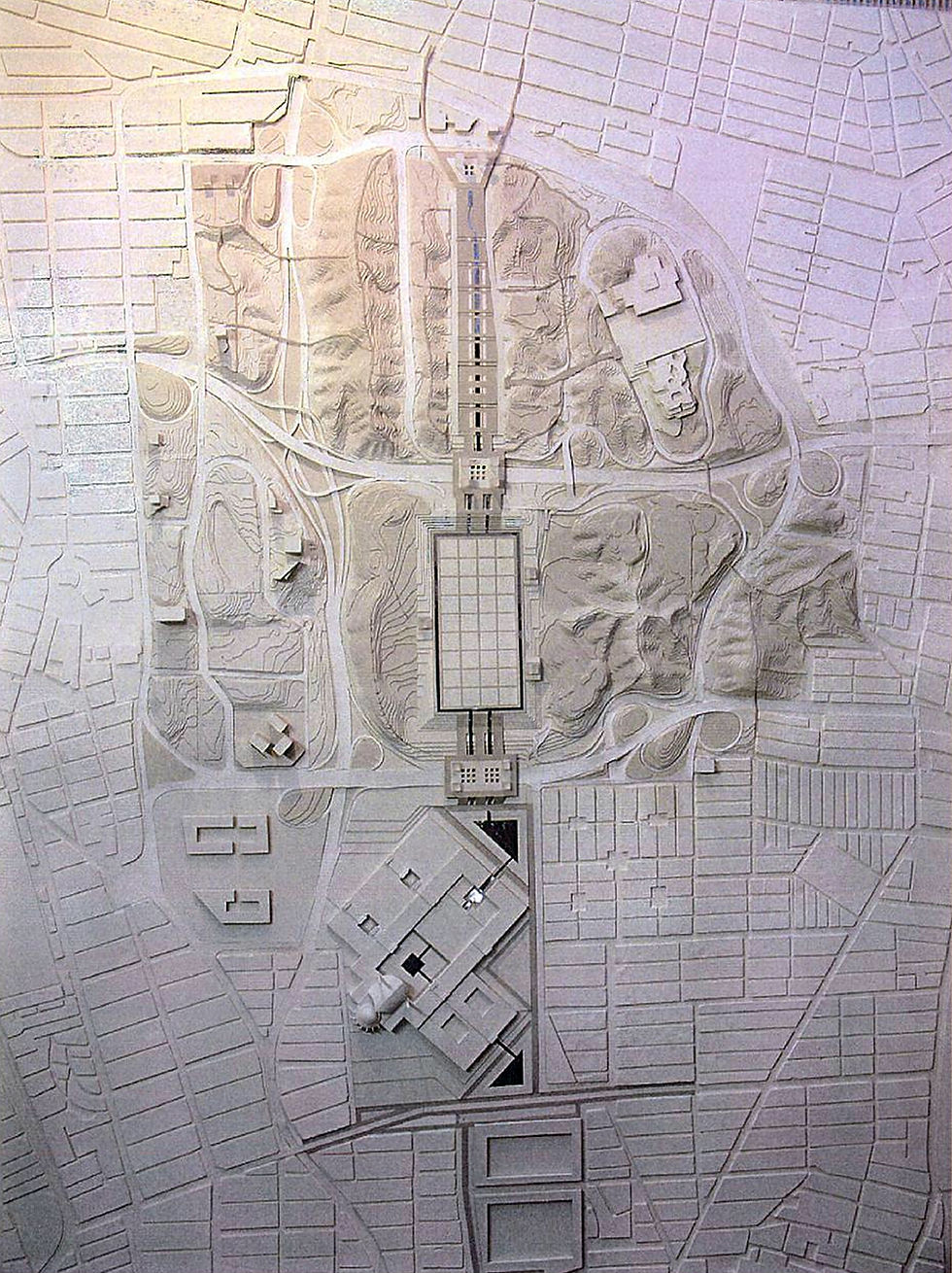

In 19th century Tehran, outside the city walls to the north, there was an arid village surrounded by the gardens of Shemiran and oases of Dawoodieh, Qasr-e Qajar and Yousefabad[4]. In the 1840s, Mollah Abbas Iravani (aka. Haj Mirza Aqasi); the Prime Minister of Mohammad Shah Qajar (r. 1834–1848), built there a garden compound with a mansion. It was known later, after his forename, as Abbasabad. These lands remained in possession of the elite and aristocrats of Qajar, up until the rise of Reza Shah Pahlavi to power (r. 1925–1941) when Bank-e Falahat (Agriculture Bank of Iran) acquired ownership of Abbasabad. In 1952, parts of the lands were devolved to the army. During the 1960s, some parts were also distributed between the Plan and Budget Organization (PBO), Bank-e Rahni-ye Iran (Iran Mortgage Bank, now known as Bank-e Maskan), and Agriculture Bank’s employees. In 1969, due to its now peculiar location in the city, the Economic Council of the PBO approved the acquisition of Abbasabad lands by facilitating bonds to be paid to private landowners.[4] This was when the city – now with more than 3 million inhabitants - stretched towards the north to surround the hills of Abbasabad and create a giant void within a dense urban fabric. Eventually, in June 1971, Abbasabad Lands Development Plan Act was passed by both the Houses of the National Assembly and the Senate. Despite its actual existence for almost three years, Abbasabad Development Corporation was officially established by Tehran Municipality in December 1974, to implement and oversee the development of the site.[4] It was around that time –– only a few years before his reign came to an end –– that Mohammad Reza Pahlavi, the last king of Iran (r. 1941-1979), dreamed of a new urban centre for his capital to be superciliously named Shahestan Pahlavi (literally the City of Shah Pahlavi). Abbasabad Lands was perfectly suited. As a result, in January 1976, the Abbasabad Development Corporation was turned into Shahestan Pahlavi Development Corporation to fulfil the aspirations of the ambitious king. The Shah ignored what the 1969 master plan of the capital had aimed for the Abbasabad district and rejected the Tehran Municipality’s plan of 1971 for his dreamland. Even the proposals drawn by renowned architects of the time, Kenzo Tange and Luis I. Kahn did not get anywhere.5 At last, in late 1974, the British planning firm, Llewelyn-Davies International (LDI) was commissioned to produce the master plan of Shahestan Pahlavi; “the largest planned city centre in the world” made up of five million square metres of floor space on ‘554 hectares’ of open land.[5]

The dream of the Shahestan never became a reality. After the Islamic Revolution of 1979, the LDI plan was halted and “only a 30-hectare parkland” (today known as Taleghani Park) remained intact on the peak of the hills.[4] In 1983, the then president of Iran, Sayyid Ali Khamenei, and Ali Akbar Hashemi Rafsanjani (the then head of the parliament) suggested that part of Abbasabad Lands be allocated for the Grand Musalla of Tehran (now known as Imam Khomeni Musalla).[4] As a result, a 63-hectare piece of land on the southern side of the site was designated for the never-ending construction of Musalla. In a letter dated April 26, 1986, addressed the Mayor of Tehran, the then president wrote that he should be informed about “any sort of interference in the lands of the [Abbasabad] region” and he suggested that the lands “should be allocated for the long-term cultural, political and also green space developments.”[4] These simply show that the revolutionary government’s desire for this relatively untouched piece of land, was no less than that of the late king.

Abbasabad Lands went through four phases of planning getting seven consultancies involved in the process. Its first post-revolutionary master plan was drawn and passed in 1998, revised in 2001 and 2004, and ultimately, the Comprehensive Plan of Abbasabad Lands drawn up by Naqsh-e Jahan Pars was approved in 2005, under the High Council of Architecture and Urban Planning.[4] Allocating the promised 63 hectares of lands for the Musalla, the master plan gives the authority of ‘559 hectares’ (nearly double the size of the City of London) to the Abbasabad Development Company.[6] But the hills of Abbasabad did not remain totally untouched while they have been busy drawing its master plan. During these years, the site was invaded by four freeways – cut through and around the hills, ‘leaving deep scars’, tearing it apart from both within and outside. This created seven fragmentary islands surrounded by a sea of asphalts. As noted, it had already been decided to build a grand mosque in the southern part. To the west of the Musalla, a 13.5-hectare piece of land became a bus terminal (Bayhaqi Bus Terminal established in 1992). Towards the north of the Musalla, a huge chunk has become home to what is now known as the Imam Khomeini Complex, containing parastatal propagandistic apparatuses such as Sadra Islamic Philosophy Research Institute, the Supreme Council of the Quran, Hosseinieh al-Zahra, Islamic Culture and Relations Organization and so on. As the official website of the latter declares, it aims at “creating and expanding knowledge, interest and belief in ‘pure’ Islam, the Islamic Revolution, […] and the Islamic-Iranian culture and civilization in other societies, so as to spread the light of Islam and strengthen the Islamic, religious and spiritual ties.”[7] Abbasabad that once was to become an entity for a political manifestation in the context of the built form, now became, to some extent, an actual locus of ideological power.

In the meantime, five gargantuan governmental towers ––including The Ministry of Road and Urban Developments, The Railways of the Islamic Republic of Iran, Bank Sepah, Tehran Provincial Government, and Ports and Maritime Organization of Iran–– were mushroomed throughout the western parts. Not to mention the construction of office blocks belonging to the Islamic Revolution Mostazafan Foundation which interestingly, still owns 130 hectares of the Abbasabad Lands.[8] This was literally the situation: the powerful state agencies and government organisations grabbed pieces of lands and built there what they desired.

As the south of the site became the location of power, the northern parts were used by members of the public. Towards the northeast, one of the seven islands, covering a total area of 100 hectares––which is nearly a third the size of the City of London–– accommodates six gigantic buildings with nearly 830,000 square metres of floor space; all served by a poorly-accessible metro station. The premises include the National Library of Iran (97,000 sqm), the Academies of the Islamic Republic of Iran (68,000 sqm), The Islamic Revolution and ‘Holy Defence’ Museum (42,000 sqm), Tehran Book Garden (65,000 sqm), Garden-Museum of the Central Bank of Iran (106,000 sqm), and the Atlas Plaza (450,000 sqm[9]). These buildings, dispersed on a vast land on the top of the hills of Abbasabad surrounded by freeways from east, north and south, are yet to become the “cultural heart of the capital”. One could say that the antiquated notion of zoning cities is yet to be practised in full swing in here. Each and every building project seems like a remote island. The buildings themselves; a bunch of free-standing, isolated structures disintegrated by the vast boulevards, are barely able to make a dialogue with each other. Filling a 100-hectare piece of land with a mere six buildings and trying to knit them together tirelessly and indeed idly, with the overly-designed so-called “conceptual gardens” has made nothing but a ludicrous mishmash of the masses and spaces. One of those “conceptual gardens” (which is now under construction) is Bagh-e Honar (Garden of Art); a jumble of nine small buildings ––‘small’ according to the Abbasabad Lands dictionary of course–– spreading throughout a 47,000 sqm piece of land including House of Poetry, House of Music, House of Architecture, Artists’ Club, Art Workshops, the Central Mansion (Kooshk-e Markazi) and so on. Walking between these buildings is profoundly uncomfortable. One feels lost and weary. It feels like walking through a temporary Expo site, or perhaps an Olympic Park which should be large enough to host hundreds of thousands of people within a short period of time. I do not tend to object to the indispensability of making places of culture and spaces of gathering, a lack of which, in fact, is what Iran’s capital suffers from. The fact is that the flâneur, never, ever comes across these public buildings. And this is actually true for the whole site of the Abbasabad Lands. Not to mention the destructive role of the existing highways which practically make a tranquil accessibility to the site almost impossible. These buildings are apparently within the city but outside of it. The spatial organisation of these projects and the way their masses have been mounted to the site, have produced an out-of-scale environment which has lost its taste of integrity and connectivity. It utterly neglected the urban fabric surrounding it. It reminds one of Makower’s words when describing the Plan Voisin: they “simply misjudged distances and the proportions of spaces needed to create a comfortable urban environment.” The very topographical nature of the Lands with the vipers of asphalt lashing around it, suggests no more than two scenarios: either leave it as it is and plant something in it, or if you will intervene, then intervene properly.

When the 2005 master plan was born, most of the projects had either been planned or were under construction. A few had even been inaugurated. One can say that it arrived too late. The master plan consists of a grand south-north visual axis of pedestrianized space that leaves the rest of the site largely for the public gardens and parks, suggesting that no more than 6.8% of the lands to be built upon. To integrate and unify the already fragmented site, it comes up with an absurd solution; it introduces two gigantic rectangular platforms which are pedestrian overpasses (one roughly four hectares and the other about one hectare), connecting the Musalla on the south to the Haghani metro station on the farthest north. Between these two overpasses it defines a colossal plaza to which the consultancy report refers as The City Grand Square which has an area of roughly 12 hectares. Its geometrical effort to be merged into the Musalla recalls the Naqsh-e Jahan Square of Isfahan ––however in a rather disproportionate manner–– where the rectangular maydān meets the angled Shah Mosque. It seems that Abbasabad desires grandiose. For the site is too large to be easily tamed. The Grand Square; an extremely enormous open air public space to be lain within an open land, conveys a manifestation of taking revenge on a city which is an oasis of cars and a paradise of highways; a city with a serious lack of public space. The Grand Square, ironically sits on a large piece of land which is highly significant to the core of Iranian power (where the Imam Khomeini Complex stands today). It asks – perhaps desperately – for demolition and relocation. The point is that the Abbasabad Development Company has never been powerful enough to be able to fully implement the approved plan. For instance, two new projects erected in recent years to the north violated the plan with consideration to their heights, the built-up area and their uses. One is the abovementioned Atlas Plaza; a colossal mixed-use development with its twin towers and a massive shopping mall. The other is the Garden-Museum of the Central Bank of Iran which has indeed transformed the semantical history of the word ‘garden’ and put the architectural vocabulary in such pain to describe its style. It was initially planned to be a place to display the national jewellery treasury of Iran sitting on a Persian Garden, instead it has appeared as a huge building a tall, bulky glass box of offices. In fact what we see here is only the tip of the iceberg. In recent years, the pseudo-private companies with strong links to the unquestionable labyrinths of power have become the key players in the process of development of the capital. They are literally beyond the government and the law.

The architecture of the Big became characteristics of the Abbasabad Lands' architectural language. One of the Bigs is Pole Tabiat (the Nature Bridge); an imposing, ostentatious, monstrous pedestrian bridge spanning over a highway, which connects two public parks of Abo Atash and Taleghani on the northwest of the site. The roughly 7,700 sqm footbridge, with a length of 270 metres and a width of 6 to 13 metres, was the result of a 2008 vaguely-processed design competition which asked for a symbolic form of architecture that is not a mere overpass, but instead, a place to stop, sit and stroll. One can contend that the controversial statement made by the Dutch architect, Rem Koolhaas – who is himself a maestro of Bigness – seems to be a factual statement when it meets the Nature Bridge: “the ‘art’ of architecture is useless in Bigness.”[10] Tabiat Bridge is literally an urban public space floating over a highway. It is indeed, an ironic metaphor of Tehran; a haven of cars condemned to hang its most symbolic public space over a freeway.

Speaking of Bigness, among many, there is Tehran Book Garden which is possibly one of the largest of its kind in the world. Disregarding the interior design of its main hall which has an air of an airport passenger terminal, one may argue over the socio-political facets of a project like Tehran Book Garden. Opening a grand book centre in a city where written words are relentlessly censored and books’ circulation has been abridged to 500, is distracting. In a city in which lamenting over the “lack of the budget” is a commonplace scene of its local authorities, instead of creating this extravagant mimicry called Tehran Book Garden – there is a mania for calling everything a ‘garden’ in this site – the money could have been spent, for instance, on the regeneration of the Enghelab Street which has been, for many years, the heart of Iran’s book industry.

As I write, the official website of the Abbasabad Lands, amazingly offers a cartoonish three-dimensional map in which it depicts the site of Abbasabad lying on a grassland on top a huge rock, floating in the sky. It is perhaps twisting around the planet earth looking for Tehran in which to land. This extraordinary metaphoric visualization of the Abbasabad Lands is indeed, precise. It genuinely shows how disintegrated it is with the actual being of the city. This is perhaps too late but worth telling; the whole site could have simply been seen as the Central Park of the city, almost twice the size of that of New York; a national landmark park with an air of a natural woodland – something analogous to the existing Taleghani Park – rather than being a jungle of banal architecture popping up in the middle of nowhere with overly-designed phony gardens and parks. Looking back at the 1975 aerial photograph of the Abbasabad Lands, it depicts an extraordinary canvas, revealing a carte blanche carved into the city fabric; a wannabe utopia; a giant vacant urban space destined to become an utter failure of city design. The urban language of the Abbasabad Lands conveys, not only how misjudgement or, say, misunderstanding of the scale may lead to a disaster, but also how the acts of a chaotic and weak urban management system can painfully be irretrievable for many years and decades. A city like Tehran with a myriad of convoluted challenges could have not borne yet another mistake in such huge scale. Trial and error should have not been on the table for that city. We need to question the authorities, planners, architects and all those who have been involved in shaping this essential part of Tehran. We need to ask why those who live in this city and they apparently are called citizens, have utterly no say whatsoever in the process. In a word, we need to turn the page and question Iran’s orthodox urbanism. There should be a political will for a bold and dramatic change in the obsolete and inefficient urban managerial structure of this country. This is an absolute prerequisite for any further development.

References

[1] Aristotle (1999) Politics. Ontario: Batoche Books.

[2] Makower, T. (2014) Touching the City: Thought on Urban Scale. Sussex, UK: John Wiley & Sons.

[3] FLC: Foundation Le Corbusier (2018) Plan Voisin, Paris, France, 1925. [Online]. Available at: www.fondationlecorbusier.fr

[4] Abbasabad Development Company (2018) Tarikhche-ye Arazi-ye Abbasabad (The History of Abbasabad Lands). [Online]. Available at: www.abasabad.tehran.ir.

[5] Emami, F. (2014) ‘Urbanism of Grandiosity: Planning a New Urban Centre for Tehran (1973–76)’, International Journal of Islamic Architecture, 3(1), pp. 69–102, doi: 10.1386/ijia.3.1.69_1

[6] Naghsh-e Jahan Pars (2005) Sanad-e Rahbordiye Tarhe Jame Araziye Abbasabad, 1384 (Abbasabad Lands Comprehensive Plan, 2005). Tehran: Naghsh-e Jahan pars Consulting Engineers.

[7] Islamic Culture and Relations Organization official website (2018) Introduction to the Organization. [Online]. Available at: www.icro.ir

[8] Donyaye Eghtesad newspaper (2018) Reclaiming 130 hectares of the Abbasabad Lands, Donyaye Eghtesad.12 April 2018, [Online]. Available at:

www.donya-e-eqtesad.com/fa/tiny/news-3375091

[9] The official website of the project’s developer: Iranian Atlas (2018) Atlas Plaza. [Online]. Available at: www.iranianatlas.ir

[10] Koolhaas, R. (1995) Bigness or the problem of Large, Monacelli Press, New York, 1995.